Brian 'Head' Welch

"Ex-Korn Guitarist Finally at Peace"

Extreme Deliverance

About This Testimony:

Ex-Korn Star Finally Finds Peace (1st Story)

The lead guitarist for the heavy metal group Korn recently shocked the music world when he announced that he was leaving the band.

Brian Welch had become a born-again Christian. He followed his announcement with a trip to Israel, where he was baptized in the Jordan River.

Welch came to the banks of the Jordan River to be baptized along with members of the Valley Bible Fellowship churches. It marked the end of one life and the beginning of another.

Pastor Ron Vietti said, "We're telling everybody that we've chosen to die with Christ. What we're doing is we're burying you. And you're dead. When you come up, [you will be] a new person like Jesus was a new person, when He was resurrected from the dead."

Welch's announcement that he became a follower of Jesus Christ rocked the heavy metal music world. Korn is one of the most popular heavy metal groups in music today. It has earned multiple platinum albums and has loyal fans around the world. But Welch says his journey from a rock star lifestyle to his new life is incomparable.

Welch said, "I've done hard drugs, I've done soft drugs. I've seen everything. I've done what teenagers dream about, especially guys. I've seen all that, and no drug or nothing compares with walking with the Lord."

Welch's visit attracted attention from press around the world, and a curious question from CNN about baptism.

CNN asked Welch, "Do you really think your whole being is going to be changed in just in a few minutes?"

Welch replied, "Yep. It's going to be changed. It's going to be changed." Watch. Interview me afterwards. You'll see. You'll see peace. I believe that."

After Welch was baptized, he told CNN, "I told you right before. Remember? I told you I was angry. I'm not angry anymore. I just want to serve God, and do what He wants me to do, and that's to teach people that this is real. I just want to see kids, whatever, come to the Lord."

Welch says God delivered him from both an addiction to methamphetamine and an empty lifestyle, a story that reminds some of the time Jesus said, he who is forgiven much, loves much.

Welch commented, "I came to Him and I seeked (sic) Him with everything I had. Everything I had. Because nothing else worked in the world. No money. I have all kinds of money, and nothing worked. And that's why this is so important to me, because He came through 100 percent."

Pastor Vietti has been a pastor for 30 years, and says Welch's faith is genuine. He remarked, "This kid's the real deal. I think if I've ever seen one, he's the real deal. He's got such childlike faith."

Vietti says Welch's testimony has already had an impact. Vietti interviewed Welch recently at Valley Bible Fellowship in Bakersfield, California. The interview, which can be seen on the church's Web site, reached a lot of people with the Gospel.

Vietti said, "We interviewed him during the service. The word got out. MTV was at church. I love it when MTV comes to church. MTV and CNN. We've been contacted, and we had about 250 people saved last Sunday. And a lot of them had Korn shirts on. Some of them drove 33 hours from Indiana. Some came from Florida. Between a half a million and a million hits on our Internet in two to three days. So it's had a bigger impact that I thought it would have."

Vietti knows the pitfalls for celebrities accepting Jesus Christ, but he hopes Christians around the world will pray for Welch. He also believes godly discipleship will be vital.

"I think it's my duty to latch onto Brian and stay close to him, and it isn't hard to do because he wants to stay close to me, and he calls me several times a day. So, I think discipleship is going to be key."

Welch has already begun writing music about his new found relationship with Jesus Christ.

Pastor Vietti believes Welch has a great potential to reach millions of young people with the Gospel.

In early 2005, Korn guitarist Brian ‘Head’ Welch’s conversion to Christianity was treated as a significant, newsworthy event.

More than 13,000 people showed up when he shared his testimony at a church in Bakersfield, California. The next day, an MTV camera crew followed him to Israel, where he was baptized in the Jordan River.

Subsequently, he traveled to India, where he opened Head Home, an orphanage for street children; he also began writing and recording his first solo album.

Subsequently, he traveled to India, where he opened Head Home, an orphanage for street children; he also began writing and recording his first solo album.

After the initial burst of interest, things settled down.

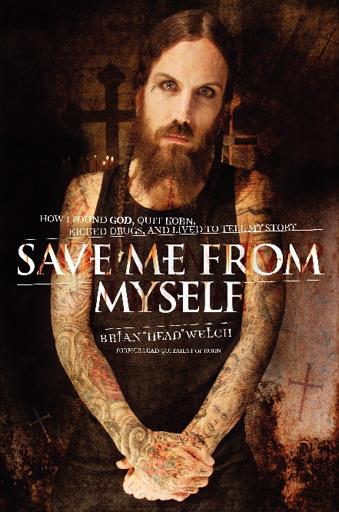

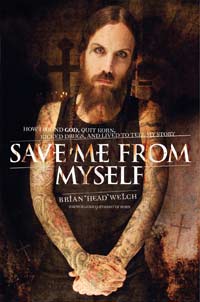

He recently released his autobiography; Save Me From Myself: How I Found God, Quit Korn, Kicked Drugs, And Lived to Tell My Story. I spoke to Welch about his life before and after, what got in the book, and a few things that didn’t.

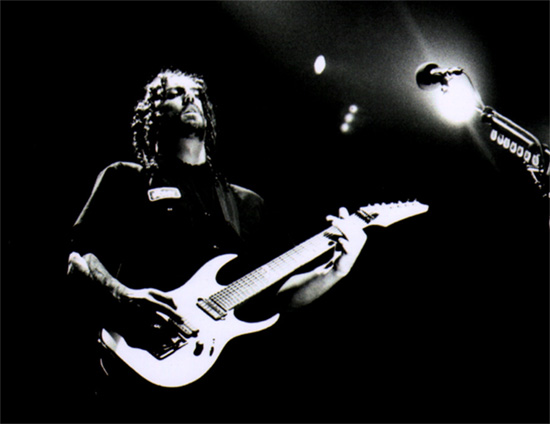

K orn is credited with popularizing nu-metal, an ingenious blend of death metal, electronica, hip hop - and in their case – bagpipes. By industry standards, they’re seasoned vets, releasing their first album back in 1994, when Seattle’s grunge bands were all the rage. Based out of L.A., their sound was even more aggressive, and netted them – at last count - nine top ten albums. Hits like ‘A.D.I.D.A.S.’ (an acronym for “All Day I Dream About Sex”) and ‘Freak on A Leash,’ have made them millionaires many times over.

orn is credited with popularizing nu-metal, an ingenious blend of death metal, electronica, hip hop - and in their case – bagpipes. By industry standards, they’re seasoned vets, releasing their first album back in 1994, when Seattle’s grunge bands were all the rage. Based out of L.A., their sound was even more aggressive, and netted them – at last count - nine top ten albums. Hits like ‘A.D.I.D.A.S.’ (an acronym for “All Day I Dream About Sex”) and ‘Freak on A Leash,’ have made them millionaires many times over.

When the band started to make money, Welch invested in real estate, and discovered he had a knack for turning a profit. Supplementing his already considerable music-related earnings, he was soon set for life.

Professionally, things couldn’t have been better, but on a personal level, his life was falling apart. His marriage had ended, leaving him a single parent, and after a decade of abuse, he was addicted to methamphetamines – speed - as well as Xanax, Vicodin, Valium and Celexa. All are potent, and highly addictive. Meth, in particular, is considered one of the hardest of all drugs to kick, with a very low recovery rate.

He had also developed a serious drinking problem; both his father and grandfather were alcoholics, making Brian at least the third generation to struggle with the disease.

After a decade in L.A., he returned to his hometown of Bakersfield in 2004, where, shortly before his conversion, he began a partnership with two local real estate developers. Both were Christians, yet rarely shared – or even spoke - about their faith with him. Nonetheless, their impact was significant.

“You know what? I saw something different. They were glowing; they had a glow about them, and they were always in good moods. They were just these guys in the real estate business, but I looked up to them for some reason. I thought it was the business and the money, because they were always wheeling and dealing, and that was my thing. Money was my god. It made me feel powerful and safe, so I wanted more and more. And that’s how awesome God is; he didn’t care that I was blind, chasing money. He still used that to get me in. It was cool.”

When he finally decided to reach out, they were there for him.

The transformation was fast, radical, and ongoing. “I dove right in; I’m like gung ho for Jesus nonstop; hours every day talking to him and just living for him. Sometimes I’m a little extreme. I’m extremist, and I take the Bible literally, I take my relationship with God very seriously. I think that’s the way it should be, you know? All or nothing.”

His friends had witnessed by simply being themselves. Others can be more obvious when it comes to sharing their faith. Welch puts himself firmly in the latter camp. “Everybody knows I’m a Christian now, because I shouted it, and I still shout it. So,” he jokes, “I beat people over the head a little bit.”

One of the first orders of business was to get straight. He’d been trying without success for years, but this time was different. He checked himself into a hotel, and detoxed in just two days. Outside of a slip one week later, he’s been clean ever since. “There’s no temptation,” he marvels. “I mean, you get thoughts, because I was addicted. You get thoughts, but I would never follow through with any actions. I’m different, man.”

He also decided to leave Korn.

He also decided to leave Korn.

It wasn’t an easy choice. The band’s roots stretched all the way back to high school, and their friendships ran deep. Taken aback by the decision, vocalist Jonathan Davis stated that he believed Brian had been “brainwashed.” Two years later, the wounds are still healing.

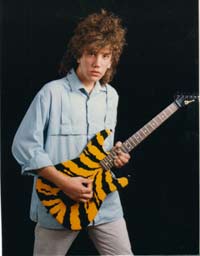

Growing up in Bakersfield, Welch’s family life was less than idyllic. Both parents worked long hours, and his father’s anger and drinking issues only made matters worse.

At ten years old, he discovered music. “I just loved it; I connected with it. It started off with Queen and Ted Nugent. And then AC/DC just blew me up. I wanted to get into music so bad after AC/DC came out with Back in Black.”

Attempting to emulate his heroes, he started taking guitar lessons. Regardless of the band, it was always heavy. More than anything else, the sheer power was what attracted him. “I didn’t connect as much with the lyrics. In fact;” he laughs, “some songs I didn’t even know what they were singing. I just loved the music. They could have been singing in Russian.”

Attempting to emulate his heroes, he started taking guitar lessons. Regardless of the band, it was always heavy. More than anything else, the sheer power was what attracted him. “I didn’t connect as much with the lyrics. In fact;” he laughs, “some songs I didn’t even know what they were singing. I just loved the music. They could have been singing in Russian.”

He lists off more early favorites, including Judas Priest, Iron Maiden, Ozzy Osbourne, Motley Crue, and, curiously, Christian metal pioneers Stryper; “I liked Stryper, too.”

He lists off more early favorites, including Judas Priest, Iron Maiden, Ozzy Osbourne, Motley Crue, and, curiously, Christian metal pioneers Stryper; “I liked Stryper, too.”

He was unaware of their rep as a Christian band; “I didn’t even know - I used to listen to To Hell with the Devil and all that stuff, and I didn’t know what it was, I didn’t connect it - that Jesus was real back then. I was like, ‘Oh, whatever, everybody sings about the devil in their songs.’ They were just another metal band.”

The group’s gospel message was completely lost on him. “When I went to their concert, I didn’t understand what they were doing, because they threw bibles [into the audience].”

The Parental Music Resource Center (P.M.R.C.) was in full swing during Welch’s formative years. As self-appointed guardians, their mission was to protect the youth of America from offensive lyrics. “They were going after rap and metal at the same time. I didn’t understand all that. I looked at them like; ‘What? Those are the people trying to ruin the party! We’re having a good time! I love that music! They’re like stuffy, boring older people.’”

He never bought the argument that metal lyrics were inherently violent and destructive. “You know, some of it was; some of it was jacked. But not all of it. Some of it was just love, and stuff like that. They weren’t singing about bad stuff.”

The P.M.R.C.’s proposal to label offensive music backfired, as bands scrambled to include warnings on their records – regardless of content - in order to boost sales. “That just hyped the thing up, and everybody had to get the CD with the explicit lyric warning on the cover; ‘You don’t understand; I need that now!’” He laughs, “Kids want to buy it more [when it’s labeled], that’s all. It’s like sin; if it says ‘Do not do something,’ then you want to do it all the more.”

The P.M.R.C.’s proposal to label offensive music backfired, as bands scrambled to include warnings on their records – regardless of content - in order to boost sales. “That just hyped the thing up, and everybody had to get the CD with the explicit lyric warning on the cover; ‘You don’t understand; I need that now!’” He laughs, “Kids want to buy it more [when it’s labeled], that’s all. It’s like sin; if it says ‘Do not do something,’ then you want to do it all the more.”

As a father, Welch’s approach to the issue is practical and matter-of-fact. “I think the parents have the responsibility to know what their kids listen to. But more importantly, be close with your kids. If you don’t take care of them – if you’re not around them all the time – then they’re going to get into some stuff.”

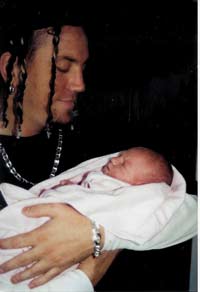

When I call for our first interview, nine year old Jeanna - who describes her father as “a plain, regular dad” - answers the phone. That’s typical, says Welch. “We’re real close, because it’s just me and her.” He’s had sole custody for years. “I work and stuff, but it’s just me and her all the time. She’s always with me, she goes from school to me.”

When I call for our first interview, nine year old Jeanna - who describes her father as “a plain, regular dad” - answers the phone. That’s typical, says Welch. “We’re real close, because it’s just me and her.” He’s had sole custody for years. “I work and stuff, but it’s just me and her all the time. She’s always with me, she goes from school to me.”

It wasn’t always that way. During his years with Korn, others cared for Jeanna while he toured and recorded. When he left the band, it was in large part due to his desire to spend more time with her.

Instead, he immersed himself in ministry-related activities, and hired a nanny to watch her. Then, the penny dropped. “I [asked myself]; ‘Wait, what am I doing? I’m doing the same things! What’s that gonna do to her? What’s that gonna teach her about God? God’s supposed to be putting families together; gluing them tight together.” He dispensed with the nanny and the two are together every day.

Staying closer to home meant reducing commitments. He parted on good terms with the ministry that runs the orphanage. “They’re still going strong…they’re doing their thing.” He downplays his part, preferring to credit others. “I donated a bunch of money to buy a home. I donated the money and that’s it. They take care of all the kids. Those nice people take care of the kids.”

Staying closer to home meant reducing commitments. He parted on good terms with the ministry that runs the orphanage. “They’re still going strong…they’re doing their thing.” He downplays his part, preferring to credit others. “I donated a bunch of money to buy a home. I donated the money and that’s it. They take care of all the kids. Those nice people take care of the kids.”

Welch and his ex-wife are the parents of two children. Their first daughter was given to an adoptive family when she was born, and when Jennea, arrived, Brian was no more prepared for parenthood. “Because I was a kid myself. Once the responsibility came, it was hard. Because I wanted to play, still. I wanted to be a kid.

Welch and his ex-wife are the parents of two children. Their first daughter was given to an adoptive family when she was born, and when Jennea, arrived, Brian was no more prepared for parenthood. “Because I was a kid myself. Once the responsibility came, it was hard. Because I wanted to play, still. I wanted to be a kid.

“Not that I’ve arrived or anything, but now, I see that we’re not here to be best buddies with them; we’re here to be their parents. And,” he stresses, “I’m a friend, too; we’re really close, but she knows, what Dad says goes. She fears Dad like I have the fear of the Lord. So,” he starts to laugh, “I’m just gonna be strict until she’s 18.”

Their relationship with his ex-wife is not what he would like it to be. “She’s got some issues going on. I’m stable with her, and when I talk to her I’m nice, but she’s up and down in her relationship with my daughter, and I need her to be solid. She goes through phases; she’ll call a lot, and want to talk to Jennea, and then she’ll disappear for a year. I don’t like that. So I put my foot down, and said ‘Okay, you gotta get yourself straightened out for a couple of years, and then we can talk.’ She’s too flaky right now, and I just gotta make the right decision that way.”

Initially, Welch believed that all earthly temptations would cease once he became a Christian. “I thought that. I thought I was going to get to go through some trials and get delivered and be healed, and then be a new man.

“Even when I was writing the book, I had a different ending, because I thought I was being healed from depression. But I’m still battling – going through the trials and tribulations and the difficult things with God. And the more that I read the Bible, [the more] I see that it’s going to stick around.

“I still go through dark days, and some are worse than others. But I know that it will pass. I mean, look at [Biblical King] David; it’s like he’s a schizophrenic or something; he’s happy one day, and upset the next. He was screaming out to God one day, and then he was joyful the next Psalm.

“Nothing’s fixed while we’re on earth. Well” - he corrects himself - “I can’t say nothing’s fixed; I don’t do drugs anymore, that’s fixed, but Ooooh, that devil gets to have his way with us sometimes. I just thank God that it’s going to be over, it’s going to pass.”

Another area that saw significant improvement was his relationship with his father. His dad had stopped drinking years earlier, but there were other, ongoing problems. “Right before I got saved, everything was coming up and bubbling out, just spilling over. Me and him were having it out. He was doing some of the same things to my daughter that he had done to me, like yelling with his angry voice, and I had just had enough.

“Then I got saved, but I was still having a hard time with him. I was thinking; ‘Jesus loves me.’ I felt the love of God…” But he didn’t feel a thing from his dad. “And I was like; ‘You didn’t love me my whole life! Get away from me!’”

Recognizing anger was not helping the situation, he prayed about it; “God’s like; ‘No. No, no, no, no.’ He taught me…”

He began to show love towards his father, and it set up a spiritual domino effect. “It’s crazy how that falls. God broke it; he just broke it, man. They ended up getting saved, and it’s like my dad’s a different person. He doesn’t drink, and I don’t drink, and we have the best relationship now - better than it’s ever been. They believe in Jesus, and they go to a Christian church. It’s awesome.”

The connection with his brother was impacted as well; “We’re really close, actually. It’s all good. They pray and their kids go to Bible camps and stuff. It’s pretty cool.”

Welch practices speaking in tongues, a subject that both his mother and brother advised him to avoid in the book. “They’re like; ‘You sure you want to put that stuff in? Everyone’s going to think you’re crazy.’”

Many denominations consider the practice an essential spiritual gift. Others avoid it altogether. For him, it’s not even worthy of debate. “It’s no big deal. It’s not something I go doing with people. It’s between me and God.

“I feel like it was big part of my deliverance, and it’s part of my life everyday now.” While it was a significant step in his own spiritual walk, he doesn’t consider it mandatory for every believer. “No. Here’s my opinion; let it be according to your faith. If you wanna do that and you believe it’s doing something for you, then it will. And if you don’t, then it won’t. You know, God meets you wherever you wanna go.”

Before the book’s release, Welch encountered ridicule and criticism from fans and former band members alike. “I got that for two years – people all over were saying; ‘He’s a nut, he’s weird.’”

He was surprised by the overwhelmingly positive reception. “I had it in the back of my mind that people were going to think that it was too harsh - the way I talk about my faith and the tongues and all that. I thought there would be more ridicule.

“But the book brings it down to street level, where they’re like; ‘Man, this guy was into drugs, he got his heart broken, divorced, all this stuff. He was messed up, man. He was hurting. And he needed help.’”

Even his former band mates have come around. “They’re all good with it. They heard rumors that I was going to bash them with a tell-all book; tell all their wild stories and personal stuff. They wrote two songs about my book, actually, on their new album. On one of them, Jonathan says; ‘I read your little book,’ and he starts laughing. But after the album came out, the book came out, and he read it, and now he’s cool with it. He’s glad I’m happy.

“The old fans, they understand me now. They understand why I came to Christ, and what happened to me. I didn’t just get weird, you know, it’s just I was broken.”

He met quite a few on the book’s promotional tour. Many were impacted – some, profoundly.

“This guy came up to me in Atlanta; he was a full-on tattooed guy, like 6’ 5”. He looked like a biker. Kind of like me,” Welch laughs, “but he came up to me, and he’s shaking. He’s like; ‘Dude, you have no idea.’ I go; ‘What?’ And he’s like; ‘I’m gonna fall down right now; I went to make fun of you on your website. I went to make fun of you and mock you, because I heard you became a Christian…and all of a sudden I got this power come on me, and all I could hear in my head was ‘Find out what’s in that book.’’

“He went to a church, found a Bible, and he got saved.” It didn’t stop there. “His wife got saved, his parents got saved, and all his friends got saved. So all these people got saved because he was going to mock me, and God just zapped him.”

They’ve stayed in touch. “He sent me a letter, he’s like full-on filled with the Holy Spirit, just loving life. He’s cool.”

With the book and subsequent promo tour completed, Welch is focusing on music again. When we speak, he’s finishing up mixing his long-delayed debut album, It's Time to See Religion Die. It’s been promised for over two years.

Listeners expecting a softer, sanitized Welch are in for a surprise. Musically, he’s stayed true to his metal roots. “Oh yeah; it’s definitely heavy.

“God cleaned me up, and he gave me these songs. They’re not all Christian-based. Some are about my old [life]: me at my worst a few years ago. It’s who I was, who I became, what I went through, and who I am now. So, kids are going to be able to relate.”

Once the album is out, the plan is to put a band together and play some live shows. As with the album’s release date, there’s no rush. “I don’t know what God’s gonna do with that. It’ll be out, though. It’s all gonna work out.”

Once the album is out, the plan is to put a band together and play some live shows. As with the album’s release date, there’s no rush. “I don’t know what God’s gonna do with that. It’ll be out, though. It’s all gonna work out.”

Welch writes on how the Lord had told him to stay out of church for a season. A primary reason for the break wasn’t disclosed in the book. Overzealous church members were sure they knew God’s will for his life better than he did. “I was getting set up with someone. They were saying that God was speaking to them, that this girl would probably be my wife. They were like; ‘Oh, you really need somebody, and this girl would be perfect, I think God spoke to me.’ And they were trying to hook me up.

“Because I’m a single dad - and they were trying to help - I went with it, and I was like; ‘Wow! God’s really doing that.’ And I went out on a couple of dates, or one date, actually, and I was like; ‘This is not God.’

It was a painful episode, and he questioned why God had put him in such an awkward situation. “I went through a lot of trials like that. I think Jesus walks us through that stuff to see if we’re going to bail on him, and see how much we really love him. He lets us get broken and stuff sometimes just to see who really loves him, and who really appreciates what he did on the cross.

“It’s just like John the Baptist. He’s told about the Messiah, he revealed the Son of God, he saw heaven open and everything, and then he’s in jail a little bit later, going; ‘Go ask him if he’s really the Messiah.’

“We walk in these positions sometimes, where we’re like, ‘Wow, why’s he letting me go through this?’” Welch has a simple explanation; “It’s our fallen nature. Only the Holy Spirit can change us into full-on, full-blown, bold men and woman of God.

“It’s crazy how personal he can become, and make the cross seem like it happened a year ago, or whenever you got saved. It’s just awesome.”

He’s no longer avoiding church. “I haven’t been for awhile, since I’ve been touring with my book and stuff, but I just got home and I look forward to going. I’m not anti-church,” he laughs, “anybody talking about Jesus, I can go and be around.”

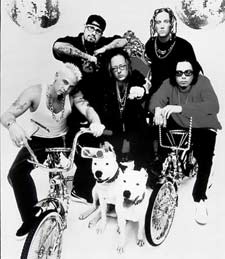

He describes Korn as “a functioning dysfunctional band.” Every member of the quintet grew up with problems at home, particularly with their fathers.

He describes Korn as “a functioning dysfunctional band.” Every member of the quintet grew up with problems at home, particularly with their fathers.

“If I think about everyone’s dad, like Munky, the other guitar player; [he] had horrible issues with his dad’s anger. The singer [Jonathan Davis]; he got massively rejected by his dad. Another guy’s dad split and wanted nothing to do with him, and we bonded that way. Especially when we were singing about it, the angst and the anger in the music maybe was powered from that, because we were all like; ‘Arghh!’” We all had that in us.

“We’re in a fallen world, and no dad is perfect anyway, but we all had issues with our dads. We didn’t talk about it when we were teenagers or anything, but it was kind of [understood].” In hindsight, he wishes they had been more open to sharing their feelings.

“You don’t let it go if you don’t deal with it. Everybody’s got issues, and if you don’t deal with them, then you’re gonna repeat the same mistakes.”

In the band’s case, after they were successful, every member’s marriage fell apart.

It’s clear he cares for them all, and in spite of some painful memories, he’s thankful for the years they spent together. “It’s crazy how God works all things for the good, that’s all I’ve got to say.”

He cites Reginald ‘Fieldy’ Arvizu, the band’s bass player, as an example; “A few months after I got saved, I called Fieldy’s dad, because he turned into a Christian when we were younger. When I was twenty or something he became a Christian; quit drinking and quit smoking. And he used to tell us that we were filled with demons and stuff like that, and it scared us off a little bit. But once I became a Christian, I tracked him down and talked to him, and he said; ‘Yeah man, I’ve mellowed out a lot, and I just want my son to be saved…he’s not saved yet, and I’ve been serving the Lord for years,’ and he said; ‘If he doesn’t get saved by the time I die, I’m gonna go right up to Jesus when I get to Heaven and say ‘Why isn’t my son saved?’”

He cites Reginald ‘Fieldy’ Arvizu, the band’s bass player, as an example; “A few months after I got saved, I called Fieldy’s dad, because he turned into a Christian when we were younger. When I was twenty or something he became a Christian; quit drinking and quit smoking. And he used to tell us that we were filled with demons and stuff like that, and it scared us off a little bit. But once I became a Christian, I tracked him down and talked to him, and he said; ‘Yeah man, I’ve mellowed out a lot, and I just want my son to be saved…he’s not saved yet, and I’ve been serving the Lord for years,’ and he said; ‘If he doesn’t get saved by the time I die, I’m gonna go right up to Jesus when I get to Heaven and say ‘Why isn’t my son saved?’”

A month later, Fieldy’s father passed away. “His dad died from an illness that just came up on him. And that night that he died, Fieldy gave his life to Jesus.”

Welch is still amazed at the turn of events. “So, it’s just like he said; he was going to Jesus, and it’s like he really did go to Jesus in Heaven, and Fieldy got saved.”

|

| Jonathan Davis with Pastor Phil |

Welch continues; “So, I went to his dad’s funeral, and I didn’t know this. He was grieving and stuff; I was crying, and I hadn’t see him since I quit Korn. I walked up to him, and not knowing he was saved, I said ‘Hey, your dad really wants you to know Jesus, man.’ I talked to him a little bit, and he was grieving. He was mad at me, and he looked at me and goes ‘You ain’t better than me! I got Jesus! You ain’t better than me!’ So it was a like a weird meeting. But now, I’ve talked to him.”

|

| Welch with Pastor Phil |

“The grace of God is smacking people like me and Fieldy and whoever else is next. We got Paris Hilton talking about Jesus after she goes to jail. Who knows if she’s saved or anything, but that’s huge. God’s moving - I just think God’s moving. And when his spirit moves, no one can resist him, because he’s irresistible. He can change the hardest dude, that’s what we’ve seen. We’ve seen it, I’ve lived it, and he changes us.

“I think that everyone’s ready for something, because you can see people get older so quickly. Their lives are flying by. Time’s passing, and people want something to be real. And I think society’s open, big time.”

Extreme Deliverance"

If you would like to receive Salvation/Deliverance, through a personal relationship with Jesus Christ or obtain information about God's Salvation Plan Click Here